Last week, I spoke to an ambitious group of high school students at SPARC in Berkeley. Several of them asked me about things I wish I had done or learned earlier in life, or regrets I had from earlier in my career. Again and again, I came back to the idea that I wish I had lived my life differently.

2006 was one of the best years for Facebook, and one of the worst years for me as a human.

I wish I had slept more hours, and exercised regularly. I wish I had made better decisions about what to eat or drink — at times I consumed more soda and energy drinks than water. I wish I had made more time for other experiences that helped me grow incredibly quickly once I gave them a chance.

You might think: but if you had prioritized those things, wouldn’t your contributions have been reduced? Would Facebook have been less successful?

Actually, I believe I would have been more effective: a better leader and a more focused employee. I would have had fewer panic attacks, and acute health problems — like throwing out my back regularly in my early 20s. I would have picked fewer petty fights with my peers in the organization, because I would have been generally more centered and self-reflective. I would have been less frustrated and resentful when things went wrong, and required me to put in even more hours to deal with a local crisis. In short, I would have had more energy and spent it in smarter ways… AND I would have been happier. That’s why this is a true regret for me: I don’t feel like I chose between two worthy outcomes. No, I made a foolish sacrifice on both sides.

This week, the tech industry has been passionately debating a recent New York Times article about Amazon’s intense work culture. Many found the article one-sided, using dramatic anecdotes to caricature a culture built around passion and intensity, while some insiders have risen to publicly defend the company. However, as far as I can tell, most people do not contest that the culture is intense and people do work really hard at Amazon. Fundamentally, this is a familiar part of tech culture: at high performing companies, employees work extremely hard, to an extent that is unsustainable for most people.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Many people believe that weekends and the 40-hour workweek are some sort of great compromise between capitalism and hedonism, but that’s not historically accurate.

Many people believe that weekends and the 40-hour workweek are some sort of great compromise between capitalism and hedonism, but that’s not historically accurate. They are actually the carefully considered outcome of profit-maximizing research by Henry Ford in the early part of the 20th century. He discovered that you could actually get more output out of people by having them work fewer days and fewer hours. Since then, other researchers have continued to study this phenomenon, including in more modern industries like game development.

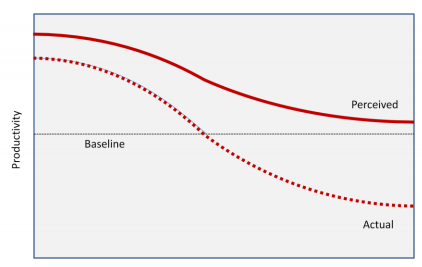

The research is clear: beyond ~40–50 hours per week, the marginal returns from additional work decrease rapidly and quickly become negative. We have also demonstrated that though you can get more output for a few weeks during “crunch time” you still ultimately pay for it later when people inevitably need to recover. If you try to sustain crunch time for longer than that, you are merely creating the illusion of increased velocity. This is true at multiple levels of abstraction: the hours worked per week, the number of consecutive minutes of focus vs. rest time in a given session, and the amount of vacation days you take in a year.

Rest matters.

[T]hese companies are both destroying the personal lives of their employees and getting nothing in return.

So it is with deep sadness that I observe the current culture of intensity in the tech industry. My intellectual conclusion is that these companies are both destroying the personal lives of their employees and getting nothing in return. A candidate recently deciding between Asana and another fast growing company told me that the other team starts their dinners at 830pm to encourage people to stay late (he’s starting here in a few weeks). I also hear young developers frequently brag about “48 hour” coding sprints. This kind of attitude not only hurts young workers who are willing to “step up” to the expectation, but facilitates ageism and sexism by indirectly discriminating against people who cannot maintain that kind of schedule.

Why are companies doing this? It must be some combination of 1/ not knowing the research 2/ believing the research is somehow flawed or doesn’t apply to them (they’re wrong) or 3/ understanding that many people see these cultural artifacts as a signal about the intensity and passion of the team. I believe it is a combination of all three factors, and the third one resonates particularly strongly with me. We’ve worked hard to build a culture at Asana where people don’t work too hard, but we sometimes have candidates tell us they are worried that means we don’t move fast enough, or have enough urgency. I’m not sure what I would do if I thought these values were actually in conflict, but fortunately they are not. We get to encourage a healthy work-life balance in the cold, hard pursuit of profit. We are maximizing our velocity and our happiness at the same time.

As an industry, we are falling short of our potential. We could be accomplishing more, and we could be providing a better life for all of the people who work in technology. If you’re going to devote the best years of your life to work, do so intentionally. You can do great things AND live your life well. You can have it all, and science says you should.

Note: I’ve written this from the perspective of the tech industry since that’s my perspective, but the pattern definitely exists prominently in other industries, and in companies across all industries.

About Author:

Dustin Moskovitz is an American internet entrepreneur who co-founded the website Facebook along with Mark Zuckerberg, Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum and Chris Hughes. In 2008, he left Facebook to co-found Asana with Justin Rosenstein.